By Maria Carmona-Montalvo and Dr. Michael Böhm

Arisbeth Ibarra Nieblas might seem low key, but she possesses a strong sense of community. Arisbeth grew up in a small town in Mexico, and, after traveling out of town for school, she eventually found herself in the U.S. pursuing a PhD at the University of Arizona.

Arisbeth grades her teachers on effort, and one gets the impression that she brings her own passionate effort to all the teaching and outreach she’s involved in. Her journey from Mexico to the U.S. brought her to the University of Arizona’s Sustainable Bioeconomy for Arid Regions (SBAR) program, where she has developed outreach activities based on a deceptively simple tenet: simple hands-on experiments are actually enjoyed the most by students. And this highlights one of her strengths; she thinks from the perspective of young learners, which is a great trait for all of us to develop. As someone great probably once said, “If you can’t explain simply then you don’t understand it fully.”

Familiarity fueled commitment

Undaunted by the two-hour bus ride, Arisbeth made the bi-weekly trek as an undergraduate to teach math and English to underserved students at a community center in the outskirts of Ciudad Obregon, Mexico. Although the community center was built by the university that she attended (Technological Institute of Sonora), her classmates would often question why she “wasted” her time going all the way to the center to teach “those” kids. Arisbeth explains that the small villages surrounding the center reminded her of her hometown, Huatabampo, Sonora, Mexico. She saw herself in the kids and wanted to help them learn basic skills that would help them succeed in life.

Paying for tuition as an undergraduate was a struggle for Arisbeth, and she often held two or three jobs in addition to being a full-time student. And although she was the first person in her family to attend college, she did not want to be the last. By making those long bus trips to teach her self-financed activities, she hoped that the kids would be inspired and get an opportunity to attend college.

During the 2020 AIChE Annual Student Conference, Arisbeth’s dedication brought her to the K-12 Showcase, where she earned second place in the professional category. The module that she presented consisted of teaching kids how to make glue from household items (water and flour) to make a piñata.

A mission begins

She started doing K-12 outreach as an undergraduate in Mexico. Her university built a community center in a low-income area of the city. She recalls seeing an email asking for college students to volunteer as instructors. Teaching came naturally to her. She remembers feeling great when she helped her younger siblings with their homework. The community center gave her free rein to teach whatever she wanted. She picked English and math because she felt those were the most practical skills that she could give her students.

Arisbeth recalls “having the best time with the students. They always shared their snacks with me and were very respectful, except I had to get them excited to do work. These classes with me were in addition to their regular schooling. I would either go twice a week or hold a mega class on Saturdays. I had students from 5 years old to 17 years old. I never missed a class. Looking back, I know so much more about teaching now, and I hope the kids had as much of a nice time with me as I did with them.”

Her work today

Today, Arisbeth is a doctoral student in environmental engineering at the University of Arizona. “My graduate research project is funded by Tucson Water and involves creating a continuous online corrosion monitoring station,” she explains. “Water quality is monitored, and the corrosion rate of metal is calculated using an electrochemical method. The project’s final aim is to install corrosion monitoring stations at various locations in Tucson’s water grid to guide the scheduling of maintenance of steel pipes, thus avoiding losing potable water to pipe leakage or bursting.”

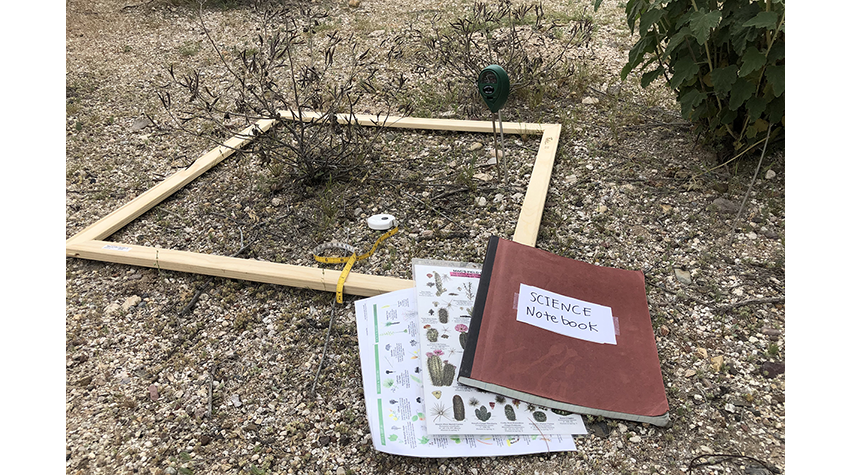

She earned an opportunity to pursue her studies through the University’s Sustainable Bioeconomy for Arid Regions program. As an SBAR Fellow, she creates educational content for middle school students, including science experiments and activities that involve complex topics like bioeconomy. She travels to schools and runs STEM activities in partnership with teachers.

Arisbeth remembers having great science instructors who may not have had the tools to teach STEM, but were nonetheless inspiring. She wants to honor all those who tried to inculcate a love of chemistry and engineering by doing the same for the hundreds of middle school students that she teaches annually.

How mentoring has taught the mentor

Arisbeth’s favorite activities with the students are when they have to make or design something. “Kids are so creative, and it is fun to see what their minds create,” she says. “My favorite activity was when I asked the students to invent a plant that could successfully grow in the Sonoran Desert, and the plant could make a bioproduct to solve a problem. The students drew the wildest plants with the most special characteristics. I enjoyed seeing what they came up with.”

She has also had activities go a bit awry. When activities didn’t go well, she believes that it was due to her eagerness; she planned to do too much. There were also times when experiments received different results with different students. However, there is one activity that she will not repeat: oil extraction from nuts and seeds. “In that activity, I divided the students into groups, and each group had a hand-cranked mill and one type of seeds or nuts — peanuts, almonds, corn kernels, etc.,” she explains. “It was really difficult for students to obtain the oil, and the process required heat to obtain the oil more efficiently. It was physically strenuous for the students, and it was a mess.” In the future she says that she would make it into a demonstration if she ever decides to repeat this activity.

Her takeaway: “Some activities can be too complex, especially when the activities require nonstandard equipment for a science classroom. Also, some of the most effective activities are some of the simplest ones. If students are asked to do a complex activity, the activity becomes the problem to solve, and the content and learning becomes the second priority.”

Professional growth through mentoring

Arisbeth says that teaching has helped her become a better researcher because it has improved her communication and presentation skills. She plans her presentations by first thinking about her audience. “When I have presented my graduate research, I have been told I present my work in a very accessible and understandable way, and I know this is thanks to my work with my students,” she says. Arisbeth also believes that she learned better time management by participating in STEM outreach activities. And she encourages other college students to take a chance on teaching the next generation of scientists because they will end up learning as much as, if not more than, they teach the kids.