Something almost magical happens when people click, ideas flow, and results surge — a perfect harmony. To the contrary, lack of team synergy, low group morale, and no tangible outcomes breed a palpable sense of demoralization within a team, and often signal that motivation has been lost.

As a leader, you might be inclined to check the wishy-washy, philosophical jargon at the door. Motivation may not feel relevant or practical. But, motivation is critical to achieving a harmonious team balance that produces results. Project teams, especially in the world of engineering, often comprise a diverse cross-section of stakeholders. It can be difficult enough to reconcile incompatible cultures and overcome language barriers, but managing conflicting personalities and communication styles presents an entirely different set of challenges. The team will look to you for clarity and direction. This article discusses why motivation matters and offers guidance on how to achieve it with your team.

What is motivation?

More than 70% of employees become disengaged every day — even to the point of contemplating quitting.(1) Considering the resources and energy required to hire and train just one individual, let alone the amount of attention required to offset just one disengaged team member, it is easy to see the importance of employee engagement. Furthermore, highly engaged employees are 38% more likely to have above-average productivity than their peers.(1) If results are your goal, deeply engaged and motivated employees are your capital for achieving that goal.

Employees must work to achieve results, but how do you get employees to do that? An old adage in our sales department is “no pain, no change” — implying that without sufficient reason to alter the process, a customer will not spend money to make a change. This maxim can be generalized to encompass all human behavior: “no motivation, no action.”

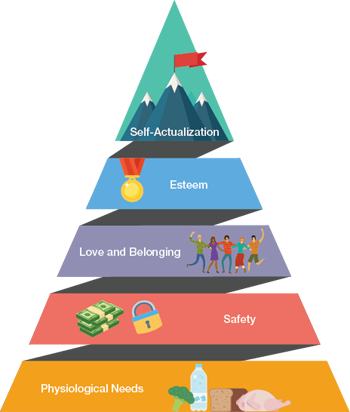

We are continually evaluating our behaviors against needs, wants, desires, obligations, and neural forces (some of which are beyond our immediate control). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs(2) has informed the basis of motivational psychology for nearly 60 years and attempts to define a path that people take to fulfillment (Figure 1).

▲Figure 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is depicted as a pyramid. Each source of motivation must be satisfied before the tier above it can be tackled. Image adapted from (2).

Maslow was on the right track with his contention that people are inherently predisposed to provide for their most basic needs (e.g., physiological needs, security, etc.). However, he did not account for a fundamental oddity of human nature — we are irrational and illogical creatures. If Maslow were correct, people would not run into burning buildings, jump out of airplanes, or leave high-paying jobs. This critical fault undermines the model and challenges academics and leaders to find new ways to address motivation.

The hierarchy misses the mark on two significant points:

- the journey to self-actualization is not necessarily linear

- yes, people can be selfish, self-serving creatures, but we will undergo some degree of suffering to accomplish a goal for which we are dedicated.

These flaws are telling. They make it clear that to encourage the right behaviors, we need to first understand the values of each individual and then establish the right environment to use those values as a motivational force for success. They also suggest that the mark of successful leaders may reside in their ability to leverage both internal and external factors that shape employee behavior.

Motivation 1.0

It is clear that we have been relying on a flawed approach to motivation, but how has that manifested in the workplace? A carrot-and-stick method has been used as a motivational tool for generations and, unfortunately, still permeates business culture.

This traditional view of motivation — let’s call it Motivation 1.0 — is predicated on the notion that the primary function of resource managers is to ensure that every part of the organization is performing at or above its required potential to ensure collective success, and that managers have an array of bureaucratic tools (e.g., quotas, bonuses, demerits, performance reviews) at their disposal to ensure compliance. In practice, this means that results are achieved or not achieved, and personnel are either rewarded or punished.

This model has worked. Tycoons made fortunes running their empires in precisely this manner. But, success comes at a price, and Motivation 1.0 also has some unintended consequences. It can prove difficult to quantify, in hindsight, the opportunity losses in terms of employee burnout, distraction, and inefficiency that result from this management style, but the dollars are real. Given an opportunity to work for an employer offering more accommodating conditions or a nominal pay increase, personnel will jump ship. Environments managed in this way are also characterized by a void of empowered accountability and creative and critical thought, which are vital in a competitive world driven by innovation.

The advent of distributed control, digital transformation, and machine learning requires a new managerial style. Monotonous, dehumanized, and decentralized tasks will be less and less the responsibility of personnel as automation advances. These actions are easy to motivate with the carrot-and-stick method, but those that are nuanced and empirical are less so. As business management has evolved, we have learned that very little human behavior transpires without emotional rationalization.

To understand how Motivation 1.0 fails today, consider an electrical engineer who enjoys software programming, from which they gain immense satisfaction and pride. To increase their output by 20%, the programmer is given an incentive of $100 per additional 10 lines of code per day. Almost immediately the programmer begins to exceed their average daily goal, helping to boost overall targets. In the following quarter, however, their output begins to trail behind past peak performance. Raising the bonus again to $200 per additional 10 lines of code might work initially, but it perpetuates an unsavory pattern of monthly declines in output and burnout of a star performer. Eventually, the engineer will stop increasing their output because $200 will no longer seem commensurate with the amount of effort.

Such incentives almost always afford immediate surges of activity. But, more subtly, this system conditions employees to expect payment for work that they initially enjoyed or were motivated to do for other reasons. A newly forged precedent to associate purpose and gratification with a rewards system has replaced pleasure that organically fueled their technical work.

As we continue to uncover the damaging effects of misapplied rewards systems on individual performance and team morale, it has become clear that a new era of intrinsic motivation is necessary to achieve sustainable results and promote employee well-being and creativity.

Motivation 2.0

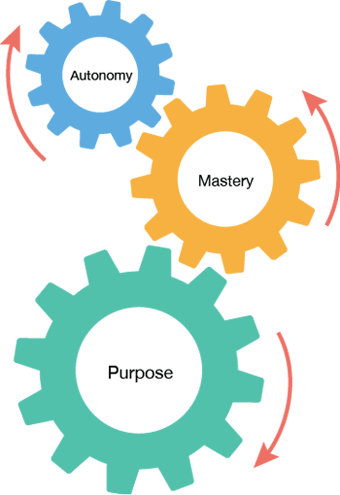

Self-determination theory (SDT), which considers inherent growth tendencies and innate psychological needs, offers a lens for looking at intrinsic and extrinsic motivators. Sovereignty over our time (autonomy), perceived success and growth in a given task (mastery), and the overall meaningfulness of that task (purpose) strongly correlate to how intensely we desire to continue and grow that behavior. When we have control over our own time, are in a position to develop and feel fulfilled, and are able to do so under a charter that aligns with our own values and beliefs, we become intrinsically motivated beyond the boundary of extrinsic rewards (Figure 2).

▲Figure 2. An organization’s purpose is often found in the mission or charter statement that broadcasts the role it aspires to serve in the marketplace, community, world, etc. An organization realizes its purpose by empowering its employees with the tools, training, and liberties necessary to produce meaningful contributions to the cause. People are, in turn, granted trust and accountability to manage and prioritize those responsibilities.

Motivation 2.0 is inspired by SDT in the same way that Motivation 1.0 was built on the Hierarchy of Needs. This new guiding principle requires looking at the individual, the leader, and the team to fully understand motivation.

Part two of this piece will appear on ChEnected tomorrow, August 3.

Literature cited

- Wakeman, C., “Reality Based Leadership,” Jossey-Bass, Hoboken, NJ (2010).

- Huitt, W., “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” Educational Psychology Interactive, Valdosta, GA (2007).

This article originally appeared in the Career Catalyst column in the July 2018 issue of CEP. Members have access online to complete issues, including a vast, searchable archive of back-issues found at aiche.org/cep.